Homogenization Overview

Homogenization Overview

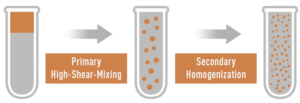

Homogenization is the process of emulsifying two immiscible liquids (i.e. liquids that are not soluble in one another) or

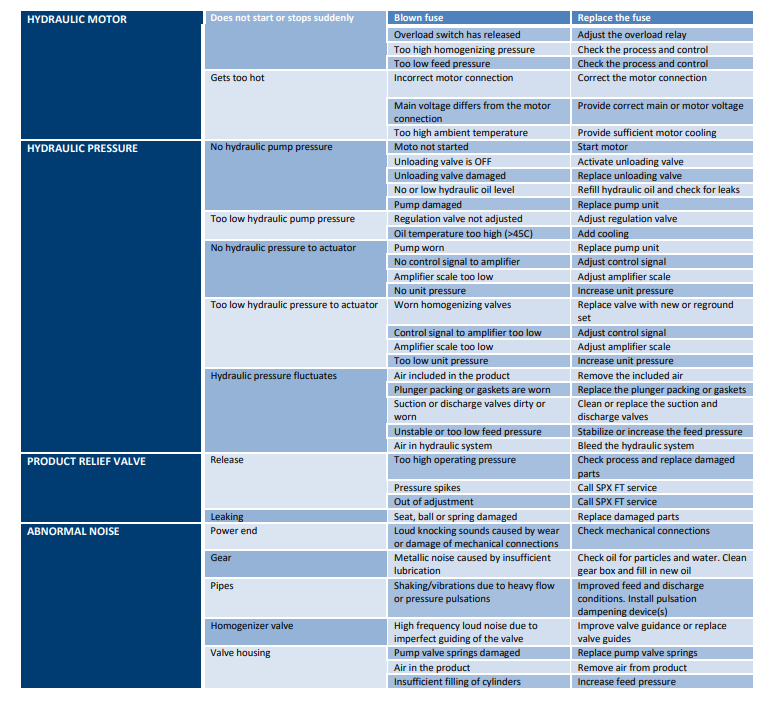

uniformly dispersing solid particles throughout a liquid. The benefits include improved product stability, uniformity, consistency, viscosity, shelf life, improved flavor and color. It has become a standard industrial process in food and beverage, chemical, pharmaceutical and personal care industries. The process of homogenization was invented and patented by Auguste Gaulin in 1899 when he described a process for homogenizing milk. Gaulin’s machine, a three-piston thruster outfitted with tiny filtration tubes, was shown at the World Fair in Paris in 1900. Since then, his name has become synonymous with homogenization. Basic emulsion formation involves adding both a surfactant and mechanical energy to join the two phases. The first step or primary homogenization involves adding surfactants or emulsifiers. Emulsions, by nature, are inherently unstable. Over time, all emulsions will eventually coalesce or “break”. Surfactants work by facilitating the creation of the emulsion and help slow down its eventual break. The resulting particle size of the globules can range in size from 0.1 to 10 microns. Emulsions change their size distribution over time, shifting to larger sizes.

The stability of an emulsion is determined by several factors including the choice of emulsifier, the phase-volume ratio, the method of manufacturing the emulsion and the temperature in both processing and storage. The order of addition, the rate of addition and the energy of the system can have a large impact on the final properties of the emulsion. Ideally, the lipophilic (oil-loving) surfactant should be dispersed in the oil phase. Finer emulsions result when the hydrophilic (water-loving) surfactant is also dispersed in the oil phase. When combining oil and water, the addition of water to the oil phase produces the finest emulsions. If the oil is added to the water phase, more energy is required to produce small droplets. A significant improvement in the emulsion can usually be seen by adding the water phase at a slower rate. Most emulsions are sensitive to the temperature of the system. Generally heat is added to the system since warm oil/fat molecules disintegrate more easily than cold ones. Micro-emulsions are a dispersion of water, oil and surfactant with particle sizes ranging from 1-100 nm. They are typically characterized as a more stable emulsion and are generally clear in appearance. They tend to have a higher concentration of surfactant relative to the oil content. These are commonly used in the pharmaceutical and personal care industries.

The Homogenizer

In today’s environment, homogenizers are used to produce more consistent emulsions in a high efficiency process. A wide variety of homogenizers have been developed to run at different pressures and capacities depending on the product mixture. In addition to product improvements, today’s homogenizers also feature reduced noise and vibration and reduced maintenance.

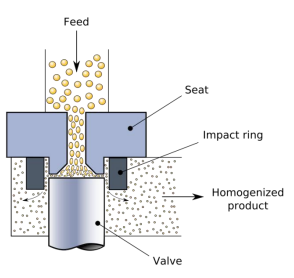

So how do homogenizers work?

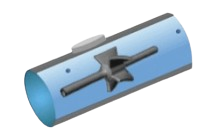

a. The non-homogenized product enters the valve seat at

high pressure and low velocity.

b. As the product enters the close (and adjustable) clearance

between the valve and the seat, there is a rapid increase in velocity

and decrease in pressure.

c. The intense energy release causes turbulence and localized

pressure differences which tear apart the particles.

d. The homogenized product impinges on the impact ring and

exits at a pressure sufficient for movement to the next step.

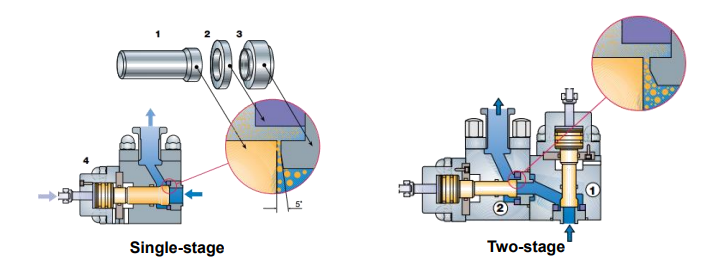

Homogenizers may be equipped with a single valve assembly (single-stage) or two valves connected in a series (two-stage). For most products, a single-stage valve is sufficient. A two-stage assembly, where ~10% of the total pressure is applied to the 2nd stage, controls back pressure and minimizes clumping. This improves the droplet size reduction and narrows the particle size distribution. Generally, two-stage

homogenization is used for products with a high fat content or products where high homogenization efficiency is required.

The valve technology is one of the most critical components of the homogenizer. Poppet valves are typically used for low-viscosity, moderately abrasive products such as ice cream, dairy, vegetable oils or silicone emulsions. Ball valves are

used for high-viscosity, abrasive products such as peanut butter, evaporated milk or wax emulsion.

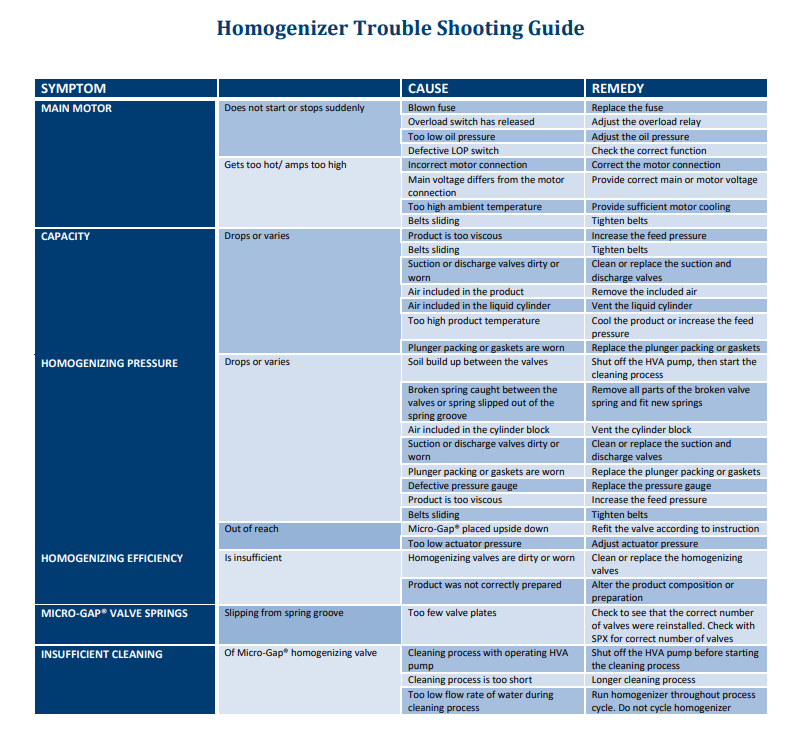

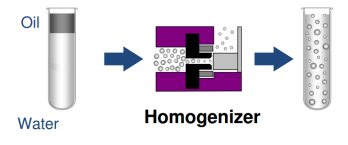

Potential Problems

To minimize potential problems with your homogenizer, one should realize that not all products are conducive to

produce in a homogenizer. If you are running one of these types of products or process conditions, you should review

the product, process and equipment with one of our technical representatives. Alternatives such as high-speed blending

or colloid mills may be recommended.

Air in the product

Heavy particles in the product

Wearing or abrasive products

High viscosity products

Aggressive products (i.e. chlorine ions)

High temperatures (max 105°C)

Low flash point products

Products with high solids content

Selecting a homogenizer

When purchasing or replacing a homogenizer, discuss the following parameters with one of our representatives.

1. Define the desired product characteristics

- What particle size and size distribution is desired?

- What is the product viscosity?

2. Define the desire production conditions

- Batch vs continuous

- Volume desired

- Temperature

3. Identify and test homogenizers

- Should I use a high-speed blender vs a high-pressure homogenizer vs a colloid mill

- Rent a homogenizer for a trial period

4. Optimize homogenization conditions

- Pressure

- Flow rate

- Time and temperature

- Emulsifier type and concentration

Flowmeters 101 – Magnetic and Coriolis

Flowmeters 101 – Magnetic and Coriolis Flowmeter

Flowmeters play a vital role in sanitary processing. They are used to measure incoming raw materials, incoming water supply, CIP solutions, ingredients in your formulation, final product production and even waste water leaving the plant. Considering their use in critical applications, ensuring that you are using the right type of meter with the correct level of accuracy for your application can be the difference in the quality of your product and save you thousands of dollars in lost revenue or profit.

In sanitary processing, one will typically find mechanical flowmeters (Positive Displacement, Turbine), electromagnetic

and Coriolis flowmeters.

Magnetic Flowmeters

Magnetic flowmeters use Faraday’s Law of Electromagnetic Induction to determine the

flow of liquid through a pipe. This type of flowmeter works by generating a magnetic

field and channeling that through the liquid in the pipe. Faraday’s Law states that flow of

a conductive liquid through the magnetic field will cause a voltage signal that can be

sensed by electrodes on the tube walls. When the fluid moves faster, more voltage is

generated. The voltage generated is proportional to the movement of the liquid.

Transmitters process the voltage signal to determine liquid flow.

The signals produced by the voltage are linear with the flow. With this, the turndown

ratio is very good without sacrificing accuracy.

Pros and Cons

Since these flowmeters measure conductivity, obviously the fluids measured need to be conductive – water, acids and

bases. Low conductive liquids, such as deionized water or gases, can cause the flowmeter to turn off and/or measure

zero flow. There is no obstruction in the path of the liquid, therefore no induced pressure drop across the meter. One

other benefit of mag meters is that they can be used on gravity-fed liquids. With gravity-fed liquids, make sure the

orientation of the flowmeter is vertical so that the flowmeter is completely filled with liquid. These flow meters are

sensitive to air bubbles because the meter cannot distinguish entrapped air from the liquid. Air bubbles will cause the

meter to read high.

Mag meters are typically chosen because they have no obstructions, are cost-effective and provide highly accurate

volumetric flow. Additionally, they can handle flow in either direction and are effective at low and high volume rates.

Coriolis Mass Flowmeters

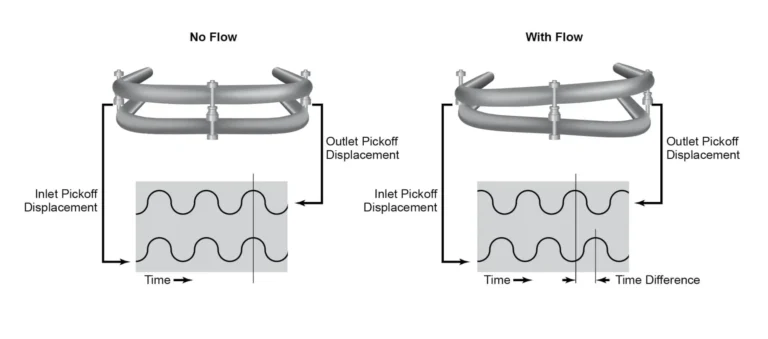

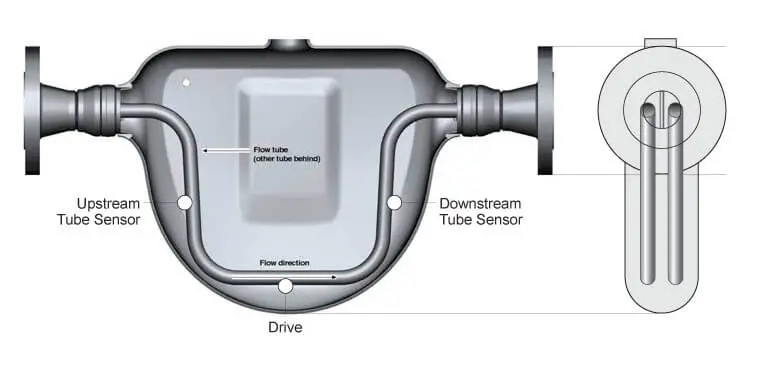

A Coriolis mass flowmeter operation is based on the principles of motion mechanics. This flowmeter contains a vibrating

tube in which a fluid flow changes in frequency and amplitude. As fluid moves through this tube, it is forced to

accelerate toward the point of peak amplitude vibration. Conversely, a decelerating fluid moves away from the point of

peak amplitude as it exits the tube. The result is a twisting reaction of the tube as flow moves through it. The amount

of twist is proportional to the real mass flow of fluid passing through the tube.

This effect can be experienced when

riding a merry-go-round – when moving

toward the center, a person will “lean

into” the rotation to maintain balance.

Most flowmeters have a split coil design.

During operation, a drive coil stimulates

the tubes to oscillate in opposition (sine

waves). A sensor measures the time

delay between the two sine waves

(Delta T) which is directly proportional to

mass flow rate.

Pros and Cons

These flowmeters are used in a wide range of critical and challenging applications. They can handle low to high flow

rates with very high accuracy. They are highly reliable and have minimal calibration requirements and low maintenance

costs. In addition, fluid density has basically no impact on flow measurement which makes Coriolis meters ideal where

the physical properties are unknown. They have a higher initial cost than other flowmeters. Pressure drop must also be

considered, especially if running high viscosity fluids.

Flowmeters 101 – Turbine and PD meters

Flowmeters 101 – Turbine and PD meters

Flowmeters play a vital role in sanitary processing. They are used to measure incoming raw materials, incoming water

supply, CIP solutions, ingredients in your formulation, final product production and even waste water leaving the plant.

Considering their use in critical applications, ensuring that you are using the right type of meter with the correct level of

accuracy for your application can be the difference in the quality of your product and save you thousands of dollars in

lost revenue or profit.

Before we begin, let’s cover a few basics of flow. Both gas and liquid flow can be measured in volumetric or mass flow

rates such as gallons per minute or pounds per minute, respectively. These measurements are related to each other by

the density of the product. In engineering terms, the volumetric flow rate is usually given the symbol 𝑸 and the mass

flow rate is given the symbol ṁ. For a fluid having a density 𝝆, mass and volumetric flow rates are related by ṁ = 𝝆 ∗ 𝑸.

In sanitary processing, one will typically find mechanical flowmeters (Positive Displacement, Turbine), electromagnetic

and Coriolis flowmeters.

Turbine Flowmeters

Turbine flowmeters use the mechanical energy of the fluid to rotate a “pinwheel” (rotor) in the flow stream. Blades on the rotor are angled to transform energy from the flow stream into rotational energy. The rotor shaft spins on bearings. When the fluid moves faster, the rotor spins proportionally faster. Shaft rotation can be sensed mechanically or by detecting the movement of the blades. Blade movement is often detected magnetically, with each blade or embedded piece of metal generating a pulse. Turbine flowmeter sensors are typically located external to the flowing stream to avoid material of construction constraints that would result if wetted sensors were used. When the fluid moves faster, more pulses are generated. The transmitter processes the pulse signal to determine the flow of the fluid. Transmitters and sensing systems are available to sense flow in both the forward and reverse flow directions.

spins proportionally faster. Shaft rotation can be sensed mechanically or by detecting the movement of the blades. Blade movement is often detected magnetically, with each blade or embedded piece of metal generating a pulse. Turbine flowmeter sensors are typically located external to the flowing stream to avoid material of construction constraints that would result if wetted sensors were used. When the fluid moves faster, more pulses are generated. The transmitter processes the pulse signal to determine the flow of the fluid. Transmitters and sensing systems are available to sense flow in both the forward and reverse flow directions.

Pros and Cons

Turbine flowmeters have a moderate cost and work well in clean, low viscosity fluids at a moderate, steady velocity. They do create some pressure drop. Bearings do wear out over time and accuracy will diminish and eventually fail as the bearings wear. Turbine flowmeters also typically work best in a limited temperature ranges. These meters are less accurate at low flow rates due to bearing/rotor drag.

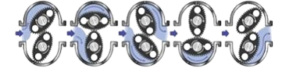

Positive Displacement Flowmeters

Positive displacement flowmeter technology is the only flow measurement technology that directly measures the volume of the fluid passing through the flowmeter. Positive displacement flowmeters achieve this by repeatedly entrapping fluid in order to measure its flow. This process can be thought of as repeatedly filling a bucket with fluid before dumping the contents downstream. The number of times that the bucket is filled and emptied is indicative of the flow through the flowmeter. Many positive displacement flowmeter geometries are available.

PD flowmeters have the same basic mechanism as a PD pump. Rotors turn to move a fixed amount of liquid through the body of the flowmeter. In most designs, the rotating parts have tight tolerances so these seals can prevent fluid from going through the flowmeter without being measured (slippage). Rotation can be sensed mechanically or by detecting the movement of a rotating part. When more fluid is flowing, the rotating parts turn proportionally faster. The transmitter processes the signal generated by the rotation to determine the flow of the fluid.

Pros and Cons

One of the main benefits of using a PD flow meter is the high level of accuracy that they offer, the high precision of internal components means that clearances between sealing faces is kept to a minimum. The smaller these clearances are, relates to how high the accuracy will be. Another benefit is the flow meters ability to process a huge range of viscosities and it is not uncommon to experience higher levels of accuracy while processing high viscosity fluids, simply due to the reduction of slippage. When considering and comparing flow meter accuracy, it is important to be aware of both ‘linearity’ i.e. the flow meters ability to accurately measure over the complete turndown ratio, and ‘repeatability’, the ability to remain accurate over a number to cycles. This is another area where PD flow meters excel, repeatability of 0.02% and 0.5% linearity are standard. Similar to a PD pump, PD flowmeters are considered to have low maintenance requirements. The moving parts will wear over time and require maintenance and calibration. They should not be used for products that contain large particles. Another factor to consider is the pressure drop caused by the PD flow meter; although these are minimal, they should also be allowed for in system calculations.

The Case of the Locking Rotors

The Case of the Locking Rotors

When the Pumps Went Silent, the Pressure Told the Truth

Detective Newell hated getting calls before coffee. This one came from one of the outside saleswomen. “Newell,” she said, voice tight. “My customers got a problem. Ten U2-006 PD pumps that are all locked up.”

Locked up pumps were never just locked up pumps. They were always a symptom—never the disease. Newell grabbed his jacket and motioned to Inspector Gauge. “Let’s go see what the pumps are trying to tell us.”

They found the pumps mounted on their sides, perched above a piece of equipment installed by another contractor. Newell didn’t like that already. Pumps, like people, don’t appreciate being put in awkward positions.

They cracked them open one by one. Same story every time.

“Notice this?” Inspector Gauge said, pointing.

Newell nodded. “One side locks up first. Always the same side.”

Back at the shop, they tore down four of the suspects. The evidence didn’t lie: rotors had kissed the cover—hard—and seized. “Running dry,” Newell muttered. “Starved.”

They told the customer as much, but the customer pushed back. “No way. That’s not it. Let’s try hot clearance rotors.”

Newell didn’t argue. He’d learned long ago that sometimes people need to walk into the truth on their own.

Before the fixes even started, the phone rang again.

More pumps.

Locked up.

Same equipment.

All twenty U2-006 PD pumps were now suspects—and victims. Newell and Gauge went back to the plant. Déjà vu. Same damage. Same story.

“You’re running them dry,” Newell said again, slower this time. The customer still wasn’t convinced. So Newell made his move. “Then let us watch them run.”

They met with an engineer and walked the process line end to end. Newell asked questions. He listened. He watched. He always watched…

“How much pressure are you seeing?” he asked.

“About 8 PSI,” the engineer replied. Newell stopped walking. “8?” He looked at Gauge. Gauge didn’t have to say anything. “That’s not just low,” Newell said. “That’s a confession.”

He told them to install temporary pressure gauges. No theories. No opinions. Just facts.

They ran the system again. Three minutes in, Newell spotted it – the centrifugal pump feeding the PD pumps wasn’t running.

“There it is,” he said quietly. “That’s the culprit.”

Newell laid it out clean and simple. “The centrifugal pump must always run first. Always.” PD pumps can’t be started without feed pressure. If a PD pump runs dry, the rotors expand, touch the cover and lock up. An improper start sequence and low PSI in the feed lines will always lead to problems.

They changed the sequence. Ran the test again. The pumps didn’t lock – didn’t squeal – didn’t complain. They just ran.

Another mystery solved. Another reminder that the correct start-up sequence is never optional. Another case where the culprit wasn’t a broken part— but bad timing, low pressure, and the truth hiding in plain sight.

The Case of Mismatched Pumps

The Case of The Mismatched Pumps

Why Serial Number Integrity Matters in Pump Gear Case Repairs

Detective Newell had seen a lot of strange cases over the years, but this one arrived in a wooden crate—six pump gear cases, stacked like silent suspects, shipped in without explanation.

At first glance, something felt wrong. As the crate was opened, Detective Newell leaned in, scanning the evidence. No covers. No bodies. No rotors. Just gear cases—bare, incomplete, and unwilling to tell their story.

At first glance, something felt wrong. As the crate was opened, Detective Newell leaned in, scanning the evidence. No covers. No bodies. No rotors. Just gear cases—bare, incomplete, and unwilling to tell their story.

“Where’s the rest of the pump?” he muttered.

A call to the customer confirmed the first clue: they only wanted the gear cases evaluated. Detective Newell did his due diligence, examining each one carefully. The verdict was clear – repairs were possible, but not without the missing pieces. Covers, bodies, and rotors would all be required to close the case properly.

That’s when the plot thickened. Detective Newell was put in touch with the head of maintenance. The conversation started simply enough, but before long, a troubling truth emerged. The missing parts weren’t lost – they were still out there, circulating.

Being used.

Mixed.

Mismatched.

Each pump, Detective Newell explained, is born with a serial number – its identity. That number is stamped on the body and the cover, binding the components together as a matched set. The rotors inside are precision-machined, each one unique, each one designed to work with its original partners.

But these pumps? Their parts had been shuffled like cards in a bad poker game.

“That’s how pumps get destroyed,” Detective Newell said, laying out the facts. “Mismatched rotors don’t forgive. They bind. They lock up. And when they fail, they fail hard.”

The evidence was undeniable. Rebuilding the gear cases without restoring their original identities would be risky – no guarantees, no alibis. The pumps might run… or they might seize without warning.

Detective Newell closed his notebook. The case was solved, but the lesson lingered: Matched parts are essential to pump reliability.

With pumps, as in detective work, the smallest details matter. Ignore identity, mix the wrong parts, and failure is only a matter of time.

Serial numbers exist for a reason—components are machined to tight tolerances and tested as a set. Ignoring that fact may keep a pump running temporarily, but it significantly increases the risk of failure.

Serial numbers exist for a reason—components are machined to tight tolerances and tested as a set. Ignoring that fact may keep a pump running temporarily, but it significantly increases the risk of failure.

Another mystery unraveled. Another reminder that precision is never optional. Proper repairs start with proper parts—and matching them correctly is the difference between long-term performance and costly breakdowns.

Weights and Scales

Weights and Scales

The measurement of ingredients in processing is fundamental. And it is important that the accuracy of the measurement is fit for purpose. In other words, it meets the requirements of the application. However, every measurement is inexact

and requires a statement of uncertainty to quantify that inexactness.

Accurate measurement enables us to:

Maintain quality control during production processes

Calibrate instruments and achieve traceability to a national measurement standard

Develop, maintain and compare national and international measurement standards

Successful measurement depends on:

Accurate instruments

Traceability to national standards

An understanding of uncertainty

Application of good measurement practice

Weighing Scales are devices that we use to determine weight. And divide into two main categories: Spring Scales and Balance Beam Scales. Balance beam type scales are the oldest type. And measure weight using a fulcrum or pivot and a lever, with the unknown weight placed on one end of the lever. And a counterweight applied to the other end. Whenever the lever is balanced, the unknown weight and the counterweight are equal.

In the 1760’s, Spring Scales introduce as a more compact alternative to the popular steelyard balance. Spring scales work based on the principal of the spring. Which deforms in proportion to the weight placed on the load receiving end. Strain gauge scales became popular in the 1960’s and used a special type of spring called a load cell.

Strain gauge scales are the most common in today’s market. But we use electronic force restoration balances in laboratory and high precision applications. Whenever we discuss weights and scales, one question is “What’s the difference between accuracy and precision?”

For example, a scale with an IP-54 Rating is “Protected against dust and splashing water”. The “5” means that protection from dust is not totally prevented. But dust does not enter in sufficient quantity to interfere with satisfactory operation of the equipment. The “4” means water splashed against the enclosure from any direction shall have no harmful effect. The highest IP rating for a scale is an IP-69K Rating. Therefore, this rating means that a strong water jet directed at the sensor from 4 directions. Must not have any harmful effects. A jet nozzle at 0°, 30°, 60° and 90° to the scale on a rotating table at 176° + 8°F. 4-6 inches away at 1250-1500psi. The test time is 2 minutes.

Shrink Processing Equipment Maintenance Costs

How To Shrink Processing Equipment Maintenance Costs

A key to keeping a processing facility running at optimum performance is routine upkeep on equipment. Preventative maintenance on your plant’s equipment is an excellent starting point to reduce costs. But there are other ways to lower overheads and keep your plant highly efficient. Here are a few questions to ask to do so.

What’s Vital, What’s Not?

Prior to making a decision to purchase processing equipment. Speak with it manufacturer and your plant’s operators and engineers about it. Be sure to discuss whether or not suggested preventative maintenance is in fact needed. As unneeded upkeep can cause equipment malfunctions. Further, be sure to review maintenance procedures annually, making any necessary adjustments as necessary. By following this strategy, your company can get the most out of its equipment while minimizing downtime caused by breakdowns.

Is Maintenance REALLY Needed?

Processing equipment manufacturers offer suggested timeframes to perform maintenance and even rebuild machines.

However, these recommendations may not be completely accurate with your facility’s needs. If a particular piece of

equipment’s manufacturer suggests maintenance every three months. But the equipment is only running for a few,

sporadic hours in that time frame, is the effort of upkeep really needed? Make sure your equipment is on a maintenance

schedule applicable to its actual use.

When’s The Best Time For Maintenance?

Routine upkeep on your facility’s equipment should be just that: on a scheduled routine. Examine the patterns of

productivity of each machine and schedule maintenance around downtimes. This will allow your plant to take

equipment out of service at a time that won’t hinder efficiency much.

Can Employees Be More Efficient?

Any time your facility can keep maintenance and repair work in house is a time of cost savings. It may be beneficial to

train employees to do these tasks on a routine basis. This will take the weight of repairs off of senior staff, and even a

paid third party. Production employees should be able to clean processing equipment, complete inspections of machines

and parts, and examine equipment for non-characteristic behavior. Should the machine begin to act in an

uncharacteristic manner. An expert should be brought in to examine the machine and plan a course of action.

Is There An Overall Upkeep Plan?

Preventative maintenance is only one form of caring for your facility’s equipment. A complete maintenance plan for

your facility’s processing equipment should include two other forms of upkeep: predictive maintenance. Using best

practices and prearranged plans to determine when a machine will need attention. And reactive maintenance,

unplanned, but necessary fixes and repairs. By using all three maintenance types together can help control costs

while maximizing production times and minimizing downtime.

Here are five tips to keep your equipment in top form:

1. Upkeep

A great place for processors to start is to simply follow the equipment manufacturers’ recommendations for planning

preventative maintenance. Regularly inspecting all of the equipment’s components, replacing worn out parts, and

upgrading various components to higher-quality alternatives can help to extend the functional life of the equipment and

avoid any costly breakdowns. Additionally, by keeping a detailed log for each piece of equipment. Processors can ensure

that preventative maintenance practices are being properly followed. Don’t forget to regularly lubricate your equipment

with the proper grade lubricant.

2. Routine Calibration

Equipment gauges can naturally fall out of alignment over time, which can cause issues such as disproportionate mixing

or inaccurate weighing of products. By regularly calibrating equipment, processors can bring gauges back into alignment

and restore accuracy throughout the production line. To be sure all equipment continues to maintain a high level of

performance. Processors should aim to regularly calibrate their equipment at least once per month.

3. Keep Extra Parts

Even with diligent preventative maintenance, equipment can still experience breakdowns. In the event of a breakdown,

processors can save valuable time and reduce operational downtime by stocking the spare parts recommended by the

equipment manufacturer. Having part replacements on hand will enable processors to get the equipment up and

running again and limit the losses of any breakdowns that may occur.

4. Operator Education

As with many elements of production, there is a right way and a wrong way for processing equipment to be operated.

Incorrect operation will likely cause unnecessary increases in wear and tear, reducing the functional life of the

equipment. Worse still, improper operation can result in outright equipment breakage, which can result in costly

replacement or repair. Spending the upfront time and cost to properly train employees is an investment that will pay off

in the long run. When operators are properly trained in the setup and orientation of processing equipment, production

efficiency can be improved and equipment will last longer.

5. Inspection

Aside from preventative maintenance and calibration, equipment needs to be inspected on a regular basis. One of the

best ways to approach inspection is to create checklists for what to look for in the way of wear and tear and inspect all

equipment components thoroughly. Although inspection may cost time, close inspection can catch potential

breakdowns before they happen, limiting downtime and mitigating repair costs.

Retention Pond Mixer – Case study

Retention Pond Mixer – Case Study

Does your plant have a basin retention pond behind the plant? If so, how does your submersible mixer and motor stand up to these harsh conditions?

A toothpaste manufacturer was struggling to find a solution for keeping their retention basins mixed. These basins are loaded with abrasive materials, wastewater, and CIP solution. As seen in the picture, their old submersible mixer and motors were struggling in this harsh environment. Therefore, Plant associates were servicing and often replacing the motors every few months. Our M.G. Newell sales associate recommended a motor from Stainless Motors, Inc (SMI). SMI is a US-based manufacturer of stainless-steel wash-down motors, gear reducers and couplings. They developed the first stainless washdown electric motor offered on the market. We took their old prop and shroud from one of their mixer setups and attached it to a new SMI stainless washdown motor. The motor has been installed and running 24/7 for nearly 2 years with NO problems and no maintenance needed. Plant personnel can simply check the amp draw for feedback on motor performance.

and CIP solution. As seen in the picture, their old submersible mixer and motors were struggling in this harsh environment. Therefore, Plant associates were servicing and often replacing the motors every few months. Our M.G. Newell sales associate recommended a motor from Stainless Motors, Inc (SMI). SMI is a US-based manufacturer of stainless-steel wash-down motors, gear reducers and couplings. They developed the first stainless washdown electric motor offered on the market. We took their old prop and shroud from one of their mixer setups and attached it to a new SMI stainless washdown motor. The motor has been installed and running 24/7 for nearly 2 years with NO problems and no maintenance needed. Plant personnel can simply check the amp draw for feedback on motor performance.

In our busy day to day operations, we sometimes lose sight of the time and energy spent on maintenance. The SMI motor was slightly more expensive in its up-front cost, however plant associates acknowledge that the ROI occurred within the first 6 months. It also means less time that they must spend digging into this muck.

In our busy day to day operations, we sometimes lose sight of the time and energy spent on maintenance. The SMI motor was slightly more expensive in its up-front cost, however plant associates acknowledge that the ROI occurred within the first 6 months. It also means less time that they must spend digging into this muck.

We realize in this “challenged” economy that everyone is

looking for ways to tighten their process parameters and keep

costs down. Contact one of our associates to see how We

Make It Work Better.

Purpose of a Calibration

Purpose of a Calibration

There are three main reasons for having instruments calibrated:

1. To ensure readings from an instrument are consistent with other measurements.

2. To determine the accuracy of the instrument readings.

3. To establish the reliability of the instrument i.e. that it can be trusted.

Traceability: relating your measurements to others

The results of measurements are most useful if they relate to similar measurements, perhaps made at a different time, a different place, by a different person with a different instrument. Such measurements allow manufacturing processes to be kept in control from one day to the next and from one factory to another. Manufacturers and exporters require such measurements to know that they will satisfy their clients’ specifications.

Most countries have a system of accreditation for calibration laboratories. Accreditation is the recognition by an official accreditation body of a laboratory’s competence to calibrate, test, or measure an instrument or product. The assessment is made against criteria laid down by international standards. Accreditation ensures that the links back to the national standard are based on sound procedures.

Uncertainty: how accurate are your measurements?

Ultimately all measurements are used to help make decisions. And poor quality measurements result in poor quality decisions. The uncertainty in a measurement is a numerical estimate of the spread of values that could reasonably be attributed to the quantity. It is a measure of the quality of a measurement. And provides the means to assess and minimize the risk and possible consequences of poor decisions.

For example we may want to determine whether the diameter of a lawn mower shaft is too big, too small or just right. Our aim is to balance the cost of rejecting good shafts. And of customer complaints if we were to accept faulty shafts, against the cost of an accurate but over engineered measurement system. When making these decisions the uncertainty in the measurement is as important as the measurement itself. The uncertainty reported on your certificate is information necessary for you to calculate the uncertainty in your measurements.

Reliability: can I trust the instrument?

Many measuring instruments read directly in terms of the SI units. And have a specified accuracy greater than needed for most tasks. With such an instrument, where corrections and uncertainties are negligible. The user simply wants to know that the instrument is reliable. Unfortunately a large number of instruments are not. Approximately one in six of all of the instruments sent to MSL for calibration are judged to be unreliable or unfit for purpose in some way. This failure rate is typical of that experienced by most calibration laboratories. And is not related to the cost or complexity of the instrument. Reliability is judged primarily by the absence of any behavior that would indicate that the instrument is or may be faulty.

Achieving Traceability in your measurements

Many quantities of practical interest such as color, loudness and comfort are difficult to define because they relate to human attributes. Others such as viscosity, flammability, and thermal conductivity are sensitive to the conditions under which the measurement is made. And it may not be possible to trace these measurements to the SI units. For these reasons the international measurement community establishes documentary standards (procedures) that define how such quantities are to be measured. So as to provide the means for comparing the quality of goods or ensuring that safety and health requirements are satisfied.

To make a traceable measurement three elements are required:

1. An appropriate and recognized definition of how the quantity should be measured,

2. A calibrated measuring instrument, and

3. Competent staff able to interpret the standard or procedure, and use the instrument.

For those who buy their measurement services from other companies. It pays to purchase from a laboratory that has been independently assessed as being technically competent to provide the measurement services.

Adjustment: what a calibration is not

Calibration does not usually involve the adjustment of an instrument so that it reads ‘true’. Indeed adjustments made as a part of a calibration often detract from the reliability of an instrument. They may destroy or weaken the instrument’s history of stability. The adjustment may also prevent the calibration from being used retrospectively. When MSL adjusts an instrument it normally issues a calibration report with both the ‘as received’ and ‘after adjustment’ values.

What a calibration certificate contains

Your calibration certificate must contain certain information if it is to fulfil its purpose of supporting traceable

measurements. This information can be divided into several categories:

it establishes the identity and credibility of the calibrating laboratory;

it uniquely identifies the instrument and its owner;

it identifies the measurements made; and

it is an unambiguous statement of the results, including an uncertainty statement.

In some cases the information contained in your certificate might seem obvious but ISO Guide 25 grew out of the experience that stating the obvious is the only reliable policy.